Desert Fury (1947): A Technicolor Noir Ahead of Its Time

Desert Fury, released in 1947, stands out as a strikingly unconventional film noir, blending vibrant Technicolor visuals with morally complex characters and a melodramatic tone. Directed by Lewis Allen and based on the novel by Ramona Stewart, the film stars Lizabeth Scott, Burt Lancaster, John Hodiak, Mary Astor, and Wendell Corey. Though not initially a major critical success, Desert Fury has since gained a cult following and critical reevaluation for its bold style, subversive undertones, and psychological depth.

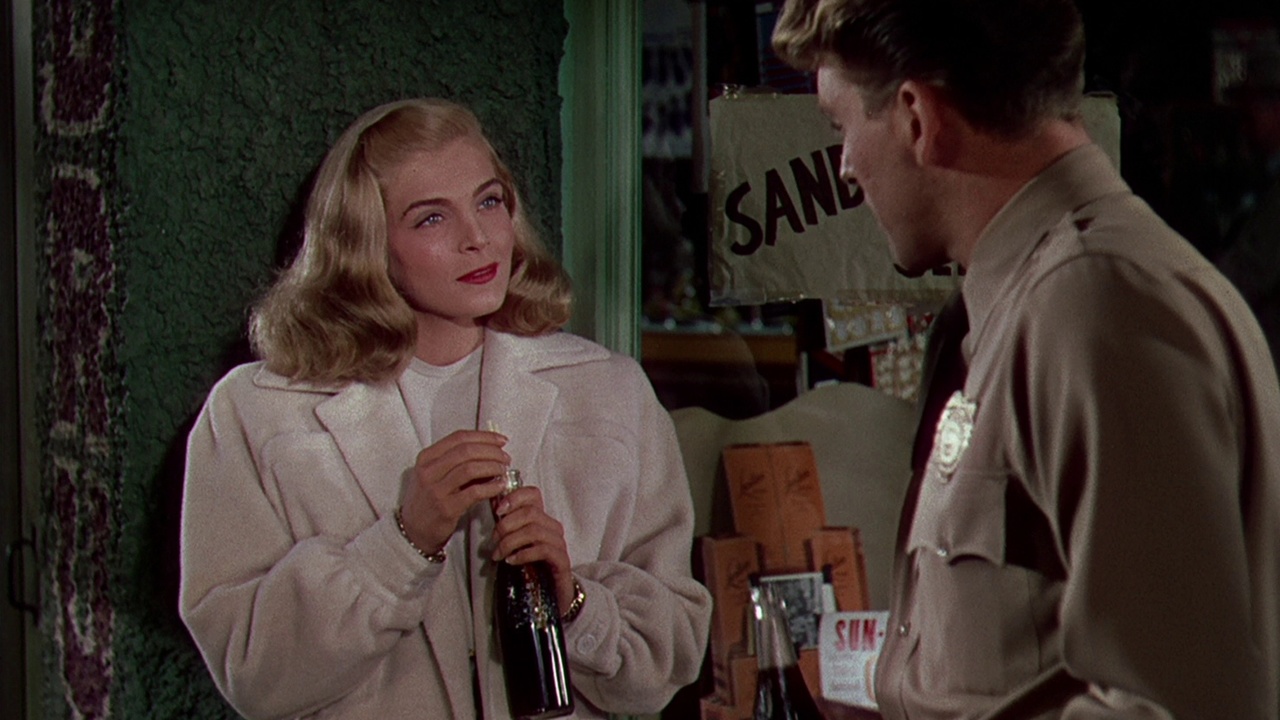

Set in a small desert town in Nevada, the story centers on Paula Haller (Lizabeth Scott), the headstrong daughter of Fritzi Haller (Mary Astor), a powerful casino owner with a shadowy past. After returning home from college, Paula becomes entangled with Eddie Bendix (John Hodiak), a smooth-talking gangster with a mysterious history—particularly concerning the death of his wife. Despite warnings from her mother and childhood friend Tom Hanson (Burt Lancaster), Paula is drawn to Eddie, setting off a chain of emotional and violent confrontations.

One of the film’s most notable features is its use of Technicolor in a genre typically defined by black-and-white shadows. Cinematographer Charles Lang's lush visuals create a surreal and almost dreamlike quality that contrasts with the grim narrative, heightening the psychological tension. The dusty landscapes, vibrant neon signs, and richly colored interiors turn the desert town into a character of its own—at once beautiful and suffocating.

The performances are equally compelling. Lizabeth Scott plays Paula with a blend of defiance and vulnerability, embodying a young woman caught between rebellion and dependence. Mary Astor, in a rare role as a morally ambiguous matriarch, delivers a commanding performance as Fritzi, who is both protective and controlling. John Hodiak is suitably menacing as Eddie, while Burt Lancaster, in an early role, brings quiet intensity to Tom, the upright lawman with his own emotional entanglements.

What makes Desert Fury particularly unique among its noir peers is its exploration of sexual ambiguity and codependent relationships. The relationship between Eddie and his henchman Johnny (Wendell Corey) is steeped in homoerotic tension—a bold implication for a 1940s Hollywood film, and one that has sparked considerable academic discussion. The film's characters are all emotionally entangled and psychologically flawed, and their motivations are often driven by longing, jealousy, and obsession rather than simple criminal intent.

Though dismissed by some contemporary critics as overly melodramatic or lurid, Desert Fury has been reevaluated in recent years as a subversive and stylistically daring work. It challenges traditional noir conventions with its visual palette, gender dynamics, and thematic risks. Film scholars and queer theorists in particular have championed it as a hidden gem that dared to hint at emotional and sexual complexities rarely acknowledged in its time.

In conclusion, Desert Fury is more than just a Technicolor noir—it is a visually arresting and thematically rich film that pushes the boundaries of its genre. With its bold performances, unusual character dynamics, and daring subtext, it remains a fascinating artifact of post-war Hollywood, deserving of renewed attention and appreciation.